Sylt, is an island in northern Germany, part of Nordfriesland district, Schleswig-Holstein, and well known for the distinctive shape of its shoreline. It belongs to the North Frisian Islands and is the largest island in North Frisia. The northernmost island of Germany, it is known for its tourist resorts, notably Westerland, Kampen and Wenningstedt-Braderup, as well as for its 40-kilometre-long (25-mile) sandy beach. It is frequently covered by the media in connection with its exposed situation in the North Sea and its ongoing loss of land during storm tides. Since 1927, Sylt has been connected to the mainland by the Hindenburgdamm causeway. In latter years, it has been a resort for the German jet set and tourists in search of occasional celebrity sighting.

GEOGRAPHY

With 99.14 square kilometres (38.28 square miles), Sylt is the fourth-largest German island and the largest German island in the North Sea. Sylt is located from 9 to 16 kilometres (6–10 miles) off the mainland, to which it is connected by the Hindenburgdamm. Southeast of Sylt are the islands of Föhr and Amrum, to the north lies the Danish island of Rømø. The island of Sylt extends for 38 kilometres (24 miles) in a north-south direction. At its northern peak at Königshafen, it is only 320 metres (1,050 feet) wide. Its greatest width, from the town of Westerland in the west to the eastern Nössespitze near Morsum, measures 12.6 kilometres (7.8 miles). On the western and northwestern shore, there is a 40-kilometre-long (25-mile) sandy beach. To the east of Sylt, is the Wadden Sea, which belongs to the Schleswig-Holstein Wadden Sea National Park and mostly falls dry during low tide.

The island’s shape has constantly shifted over time, a process which is still ongoing today. The northern and southern spits of Sylt are exclusively made up of infertile sand deposits, while the central part with the municipalities of Westerland, Wenningstedt-Braderup and Sylt-Ost consists of a geestland core, which becomes apparent in the form of the Red Cliff of Wenningstedt. The geestland facing the Wadden Sea gradually turns into fertile marshland around Sylt-Ost. Today sources show that Sylt has only been an island since the Grote Mandrenke flood of 1362. The so-called Uwe-Düne (Uwe Dune) is the island’s highest elevation with 52.5 metres (172.2 feet) above sea level.

The island in its current form has only existed for about 400 years. Like the mainland geestland, it was formed of moraines from the older ice ages, thus being made up of a till core, which is now apparent in the island’s west and centre by the cliff, dunes and beach. This sandy core began to erode as it was exposed to a strong current along the island’s steep basement when the sea level rose 8000 years ago. During the process, sediments were accumulated north and south of the island. The west coast, which was originally situated 10 kilometres (6 miles) off today’s shore, was thus gradually moved eastward, while at the same time the island began to extend to the north and south. After the ice ages, marshland began to form around this geestland core.

In 1141, Sylt is recorded as an island, yet before the Grote Mandrenke flood it belonged to a landscape cut by tidal creeks and, at least during low tide, it could be reached on foot. It is only since this flood that the creation of a spit from sediments began to form the current characteristic shape of Sylt. It is the northern and southern edges of Sylt which were, and still are, the subject of greatest change. For example, Listland was separated from the rest of the island in the 14th century and from the later 17th century onwards the Königshafen (King’s Harbour) began to silt up as the “elbow” spit began to form.

In addition to the constant loss of land, the inhabitants during the Little Ice Age were constrained by sand drift. Dunes shifting to the east threatened settlements and arable land and had to be stopped by the planting of marram grass in the 18th century. Consequently, though, material breaking off the island was increasingly washed away and the island’s extent continued to decrease.

Records of the annual land loss exist since 1870. According to them, Sylt lost an annual 0.4 metres (16 inches) of land in the north and 0.7 metres (28 inches) in the south from 1870 to 1951. From 1951 to 1984, the rate increased to 0.9 metres (35 inches) and 1.4 metres (55 inches) respectively, while shorelines at the island’s very edges at Hörnum and List are even more affected.

Severe storm surges of the last decades have repeatedly endangered Sylt to the point of breaking in two, e.g. Hörnum was temporarily cut off from the island in 1962. Part of the island near Rantum which is only 500m wide is especially threatened.

Measures of protection against the continuous erosion date back to the early 19th century when groynes of wooden poles were constructed. Those were built at right angles into the sea from the coast line. Later they were replaced by metal and eventually by armoured concrete groynes. The constructions did not have the desired effect of stopping the erosion caused by crossways currents. “Leeward erosion”, i.e. erosion on the downwind side of the groynes prevented sustainable accumulation of sand.

In the 1960s breaking the power of the sea was attempted by installing tetrapods along the groyne bases or by putting them into the sea like groynes. The four-armed structures, built in France and many tons in weight were too heavy for Sylt’s beaches and were equally unable to prevent erosion. Therefore, they were removed from the Hörnum west beach in 2005.

Since the early 1970s the only effective means so far has been flushing sand onto the shore. Dredging vessels are used to pump a mixture of sand and water to a beach where it is spread by bulldozers. Thus storm floods would only erase the artificial accumulation of sand, while the shoreline proper remains intact and erosion is slowed down. This procedure incurs considerable costs. The required budget of an annual €10 million is currently provided by federal German, Schleswig-Holstein state and EU funds. Since 1972 an estimated 35.5 million cubic metres of sand have been flushed ashore and dumped on Sylt. The measures have so far cost more than €134 million in total, but according to scientific calculations they are sufficient to prevent further loss of land for at least three decades, so the benefits for the island’s economic power and for the economically underdeveloped region in general would outweigh the costs. In the 1995 study Klimafolgen für Mensch und Küste am Beispiel der Nordseeinsel Sylt (Climate impact for Man and Shores as seen on the North Sea island Sylt) it reads: “Hätte Sylt nicht das Image einer attraktiven Ferieninsel, gäbe es den Küstenschutz in der bestehenden Form gewiss nicht” (If Sylt did not have the image of an attractive holiday island, coastal management in its current form would certainly not exist).

The enforcement of a natural reef off Sylt is being discussed as an alternative solution. A first experiment was conducted from 1996 to 2003. A sand drainage as being successfully used on Danish islands is not likely to work on Sylt owing to the underwater slope here.

In parallel to the ongoing sand flushing, the deliberate demolition of groynes has begun amid great effort at certain beach sections where they were proven largely ineffective. This measure also terminated the presumably most famous groyne of Sylt, Buhne 16 — the namesake of the local naturist beach.

A number of experts, however, fears that Sylt will still have to face considerable losses of land until the mid 21st century. The continuous global warming is thought to result in increasing storm activity, which would result in increased land loss and, as a first impact, might mean the end of property insurance. Measurements showed that, unlike in former times, the wave energy of the sea is no longer lost offshore, today it carries its destructive effects on to the beaches proper. This will result in an annual loss of sand of 1.1 million m³. The dunes of the island constitute nature reserves and may only be traversed on marked tracks. So called “wild paths” promote erosion and are not to be followed. Where vegetation is tread upon, no roots are left to hold the sand and it will be removed by wind and water.

The Wadden Sea on the east side between Sylt and the mainland has been a nature reserve and bird sanctuary since 1935 and is part of the Schleswig-Holstein Wadden Sea National Park. The construction of breakwaters in this area will abate sedimentation and is used for land reclamation.

Also the grazing of sheep on the sea dikes and heaths of Sylt eventually serves coastal management, since the animals keep the vegetation short and compress the soil with their hooves. Thus they help create a denser dike surface, which in case of storm surges provides less area for the waves to impact.

CLIMATE

On Sylt, a marine climate influenced by the Gulf stream is predominant. With an average of 2 °C, winter months are slightly milder than on the mainland, summer months though, with a median of 17 °C, are somewhat cooler, despite a longer sunshine period. The annual average sunshine period on Sylt is 4.4 hours per day. It is due to the low relief of the shoreline that Sylt had a total of 1,899 hours of sunshine in 2005, 180 hours above the German average. Clouds cannot accumulate as quickly and are generally scattered by the constant westerly or northwesterly winds.

The annual mean temperature is 8.5 °C. The annually averaged wind speed measures 6.7 m/s, predominantly from western directions. The annual rainfall amounts to about 650 millimetres. Since 1937 weather data are collected at Deutscher Wetterdienst’s northernmost station on a dune near List, which has meanwhile become automated. A number of commercial meteorological services like Meteomedia AG operate stations in List too.

Sylt features an oceanic climate that is influenced by the Gulf Stream. On average, the winter season is slightly warmer than in mainland Nordfriesland. The summer season, however, is cooler despite of longer sunshine periods. The yearly average sunshine period is greater than 4.4 hours per day with some years exceeding the average sunshine for all of Germany. Also precipitation is lower than on the mainland. This is due to the low relief of Sylt’s shoreline where clouds are not able to accumulate and rain off.

HISTORY

Geographically, Sylt was originally part of Jutland (today Schleswig-Holstein and mainland Denmark), with evidence of human habitation going back to 3000 BC at Denghoog. The first settlements of Frisians appeared during the 8th century and 9th century. In 1386, Sylt was divided between the Duke of Schleswig and the King of Denmark; except for the village of List, Sylt became part of the Duchy of Schleswig in 1435.

During the 17th and 18th century, whaling, fishing and oyster breeding increased the wealth of the population. At this time, Keitum became the capital of the island, and a place for rich captains to settle down. In the 19th century, tourism began. Westerland replaced Keitum as the capital. During World War I, Sylt became a military outpost. On 25 March 1916 British seaplanes bombed the German airship sheds on Sylt. In 1927, a rail causeway to the mainland was built, the Hindenburgdamm, named after Paul von Hindenburg. During World War II, Sylt became a fortress, with concrete bunkers built below the dunes at the shore, some of which are still visible today. Lager Sylt, the concentration camp on Alderney was named after the island. Rudolf Höss hid on the island after Nazi Germany’s defeat, but he was later captured and brought to trial in Poland.

Today, Sylt is mainly a tourist destination, famous for its sandy beaches and healthy climate. The 40 km-long (25 mi) west beach has a number of surf schools and also a nude section. The Windsurf World Cup Sylt, established in 1984, is annually held at Westerland’s beach front. Sylt is also popular for second home owners, and many German celebrities who own vacation homes on “the island”.

CULTURE

Sylt is a part of the Frisian Islands. It has its own local dialect, Söl’ring, which is the indigenous speech of Sylt. Söl’ring is a dialect of insular North Frisian, with elements of Danish, Dutch and English. Today, only a small fraction of the population still speak Söl’ring. A law to promote the language (Friesisch-Gesetz) was passed in 2004. The northernmost part of the island, Listland, was traditionally Danish-speaking.

As in many areas in Schleswig-Holstein on New Year’s Eve, groups of children go masked from house to house, reciting poems. This is known as “Rummelpottlaufen”, and as a reward, children receive sweets and/or money.

Sylt also features many Frisian-style houses with thatched roofs.

The name of the island in standard German uses “y” for unknown reasons; the expected spelling would normally be “Sült”.

TRANSPORT

Sylt is connected to the German mainland by the Hindenburgdamm, a causeway with a railway line on top. The passenger trains connect Westerland (Sylt) to Niebüll or Klanxbüll, and the Deutsche Bahn’s “Syltshuttle” allows the transfer of cars and trucks between Westerland and Niebüll. There are also ferry services to the nearby Danish island of Rømø. Sylt Airport at Westerland serves the region.

Wheather you prefer a comfortable flight to Sylt from many directConnections europ wide, or if you prefer to bring your vehicle and cross the Wadden Sea by ferry or train, there are many options to get on the Iceland.

Here you find some useful information about how to get on the Iceland.

By Car

If you choose to go by car, you want to cover the load leg of your journey by motor rail. After you board the train in Niebüll, a 40-minute ride over the causeway Hindenburgdamm will take you across the tidal flats to Westerland.

By Train

If you prefer leaving your car at home, you can reach Sylt comfortably by train. There are Several directConnections from Hamburg as well as inter-city connections from other big cities every day.

By Airplane

The fastest way to get to Germany’s most famous holiday Iceland is by air. There are scheduled flights from various German cities. International connections are possible with AirBerlin and Lufthansa. Sylt’s airport is located in the heart of the Iceland.

By Ferry

Alternatively, you can travel by sea: a modern ferry carries Both passengers and vehicles from Rømø, Sylt’s Danish Neighbouring Iceland, to List. The mini-cruise across the North Sea takes about 40 minutes.

Activities

Rotes Kliff Rotes Kliff |

Golf Club Budersand Golf Club Budersand |

Lister Wanderduenen Lister Wanderduenen |

Südkap Surfing Surfschule Südkap Surfing Surfschule |

Tierpark Tinnum Tierpark Tinnum |

St. Severin, Keitum St. Severin, Keitum |

Morsum-Kliff Morsum-Kliff |

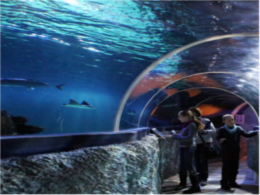

Sylt Aquarium Sylt Aquarium |

Accommodation

Car Rental

SYLT BEACHES

Those looking for peace and quiet will find it off the central beaches; naturists can skinny-dip and sunbathe among the like-minded; dog owners and their Fidos can frolic on designated dog beaches; and windsurfers can ride the waves in the best surfing spots. There are often no clear-cut boundaries between these beaches, and Sylt and its visitors have a reputation for being quite tolerant.

Westerland’s “Fun-Beach Brandenburg” bustles with life. In high summer, the place is bursting at the seams – much to the pleasure of our numerous young visitors who enjoy playing sports and being where the action is. Beach soccer and volleyball, bowling greens and dartboards are only some of the many attractions, making sure there is never a dull moment. And every Friday at 2 pm, the Beach Olympics draw athletes to the sand stadium to compete under the motto ‘Let’s have fun!’ and ‘It’s taking part that counts!’

Further south towards Rantum, beach names like “Oase zur Sonne”, “Samoa” and “Sansibar” promise exoticism.

The family-friendly main beach of Hörnum, easily accessible via the promenade, boasts a special attraction. It is overlooked by a widely visible red-and-white lighthouse, which can be visited by appointment.

Tucked away behind an unspoilt dune landscape, List’s west beach in the island’s north offers a secluded stretch of seashore, where those looking for rest and relaxation will feel especially at home. However, the young entertainment-seeking generation is not left high and dry either: on their own stretch of beach, kids and teenagers can romp around and make noise to their heart’s content.

Once as famous as it was infamous, Kampen’s Buhne 16 (‘Buhne’ means ‘groyne’) is still legendary. Today, top managers sunbathe side by side with blue-collar workers, large families next to soap stars. There are no social barriers; after all, “In swimming trunks, everyone looks pretty much the same anyway.”

The beach access point at the Red Cliff affords spectacular views of the sea. The viewing platform is wheelchair-accessible.

Wenningstedt is not only popular for its wide main beach. At the northern beach access point, generally referred to as “at Wonnemeyer’s” or “Abessinia”, a big play-ship fascinates little visitors.